I want to tell you a story about a song.

But first, I want you to hear it for yourself.

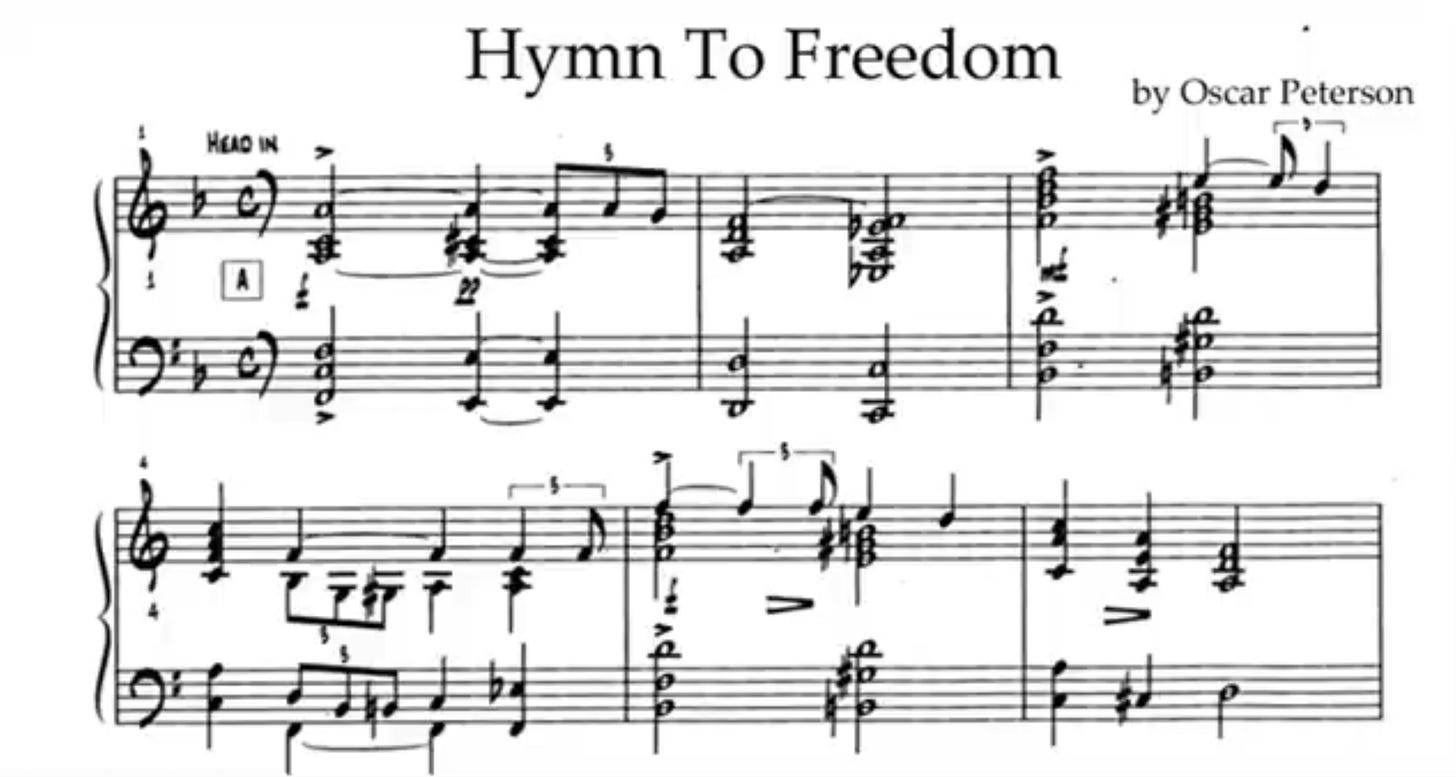

▶️ Watch “Hymn to Freedom” by Oscar Peterson.

Watch the black-and-white footage. You’ll know it when you see it: a simple stage, a modest piano, and Oscar Peterson seated with the quiet authority of someone who’s got nothing to prove—and everything to offer. The piece is called Hymn to Freedom, and it begins not with a fanfare, but with a pause. A breath. A chord that lands like the beginning of something sacred.

That first note holds a weight you can’t explain. It doesn’t announce itself—it enters like a memory. And from there, Peterson doesn’t just play. He builds. He walks us through something—deep and deliberate, spiritual but unmistakably human.

This wasn’t background music. This was 1962. The streets of Birmingham were burning, the March on Washington was still a dream, and Peterson’s best friend and producer, had just asked him to compose something “with a definitive early-blues feel.” Instead, Oscar wrote this.

Inspired by the bare, raw and real spirituals he heard in Montreal’s Black churches as a child, Peterson rooted the opening chorus in the call-and-response feel of a Baptist hymn. But what emerged was something larger: a blessing in twelve bars. A gospel of dignity. A meditation in motion.

Within months, Hymn to Freedom was embraced by the Civil Rights Movement—not by marketing push or industry hype, but because the people knew what they were hearing. They knew this wasn’t just jazz. This was a mirror. A balm. A call.

To this day, you can feel that resonance. The piece doesn’t rush. It returns. Over and over. Like the bell in the meditation hall or a mantra in your bloodstream.

That’s insight too. Not some grand revelation, but the quiet discipline of returning. Returning to the breath. Returning to the body. Returning to what’s here. Over and over—until the truth begins to reveal itself in the repetition.

Ralph Ellison once wrote, “The blues is an autobiographical chronicle of a personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.” And Oscar knew that. He understood that beauty wasn’t the opposite of suffering—it was a response to it. Hymn to Freedom doesn’t erase pain. It dignifies it. It says: we’ve been through something—but we are still here. And we can still play.

Before I offer a Dharma talk, I sit. That part is non-negotiable. The sitting is what roots me—not just in presence, but in lineage. In rhythm. In truth. And sometimes, during that quiet before the offering, I hear music. Not always—but often enough. On certain days, it’s Hymn to Freedom. I put it on, and listen—deeply. Not for inspiration, but alignment. I draw on its steadiness, its sorrow, its devotion to what’s real and upright. The time it keeps slows my pulse, clears my mind. It’s not just music—it’s a kind of preparation. A practice. There’s something in it that meets the Dhamma at the level of essence. Something encoded—ancestral, devotional, uncompromised—that helps me remember why I teach at all.

Because that’s what this piece is. It’s samadhi braided with sorrow. It’s suffering that doesn’t collapse—it keeps time. It doesn’t strip away the spirit—the heart of it all. It shows how the heart endures, and how the groove survives.

You could say the three characteristics live in this song—annica in the tempo, dukkha in the chords, anatta in the way Oscar fades into the music. But you don’t have to name them to feel them. They’re there, pulsing in the phrasing. Offered without claim.

It’s the sound of renunciation, not as austerity, but as elegance.

Peterson was a Black man and a Canadian—none of which he ever downplayed. He carried that identity with clarity, not performatively. He knew the racial dynamics of the States from the outside in. And yet, he chose to stand with the Movement. To lend his hands, his name, his art.

And maybe that’s part of why Hymn to Freedom hits differently right now. Because here we are, in a moment of sharp tension—where the U.S. government, in its current posture, has turned antagonistic toward longtime allies and neighbors to the north. It’s petty, performative posturing—dangerous not just in tone, but in impact.

And yet—Peterson once said:

“If you have something to say of any worth then people will listen to you. You not only have to know your own instrument, you must know the others and how to back them up at all times.”

That’s not just musical advice. That’s a civic ethic. That’s sangha in action. That’s what Dharma on this continent looks like when it remembers: we’re not soloists. We’re a collective improvisation. And freedom—real freedom—requires deep listening and mutual backing.

Jazz has long carried that wisdom. It’s why so many of its greatest players found their way to the various schools of Buddhism. From Herbie Hancock and Joseph Jarman to Wayne Shorter, they understood that to improvise well, you need presence. Discipline. Spaciousness. You need to know when to play—and when to stop.

There’s a whole tradition of writing about jazz that treats it as magic. But the best jazz writing? It doesn’t mystify—it dignifies. It names the craft, the sweat, the structure. It doesn’t strip away the spirit—the heart of it all. It shows how the heart endures, and how the groove survives.

Hymn to Freedom is one of those surviving things.

Not frozen in amber, but living. Breathing.

Its lyrics—rarely sung, but still stirring—speak of every heart joining every heart, every hand joining every hand. It’s not utopia. It’s aspiration. A North Star, not a resting place. And every time I hear it, I’m reminded that liberation isn’t abstract. It’s a sound. It’s a movement. It’s what happens when dignity and solidarity begin to harmonize.

So yes. Watch the video. Not for nostalgia—but for insight. Watch Oscar’s hands. Watch the way the audience leans in. Watch how nothing is rushed, nothing is wasted. That’s Dharma. That’s integrity. That’s liberation in tempo.

And then—sit for a while.

Not to analyze. Just to listen.

Because in this moment, that may be the most radical act we have left.

Not shouting. Not scrolling. Not outrunning.

But listening.

Listening to the places in us that still long to be free.

Because sometimes, the story isn’t in the telling.

It’s in the hearing.

Still listening, in rhythm, refuge, and freedom—

Devin

devinberry.org | Heartstream Sangha

IG: @blkb3rry

Upcoming Retreat

August 27–31, 2025

Big Bear Retreat Center

BIPOC Retreat with Devin Berry, Alli Simon, Hakim Tafari, and JoAnna Hardy

A spacious, grounded refuge for healing, deep practice, movement, and connection.

Thank you Devin, so beautiful !

Your words and the music nourish my heart, my freedom 🙏

Thank-you for sharing this gift of music and for holding this space.